In the summer of 2013, Leslie Schwartz will be awarded The Knight's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. In the summer of 1944, he lost his entire immediate family when he was just fourteen years old and they were caught up in the mass deportations of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, the death camp in Poland where over one-million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust. Almost year had passed and Schwartz had managed to survive Auschwitz (he was there for about ten days) and later sub-camps of Dachau and Muhldorf, but by VE (Victory in Europe) day, May 8, 1945, Schwartz was hardly in a mood to celebrate. He was liberated by American troops near Tutzing, the famous resort town in Bavaria, after having been an unwilling passenger on the so-called Muhldorf death train where roughly three-thousand mostly Hungarian Jews who had been imprisoned at Muhldorf were marched out of the town on April 25, 1945 and then forced onto a long, slow-moving train, designed to bring them to their deaths, thereby eradicating any possibility of survivors or witnesses to the atrocities. A few days into the ride, April 27, 1945, Schwartz was shot in the head by a member of the Hitler Youth in a field in Bavaria. The train had either broken down or rumors of the war's end had frightened the SS Guards into stopping the train, and for a few hours many of the prisoners temporarily escaped, fleeing toward the rural town of Poing. Despite the head wound, the bullet had entered his neck and excited his face, he was marched back to the tracks as the SS forced the survivors of the massacre to throw many of the dead and critically wounded back into the cattle cars. The rest of the ride to nowhere featured strafing by American fighter pilots thinking the cars were transporting German troops of some kind. Schwartz remembers pulling dead bodies over his to shield him from bullets, which were flying everywhere. In addition to his his shattered jaw, he was infected with Typhus, homeless, without citizenship in any country, no immediate family, and only the clothes (a prison uniform) on his back--after almost a year in the camps, his weight had dropped to about seventy-five pounds. What were the odds that he would survive beyond a few days much less be honored by Germany sixty-eight years later?

Bundesverdienstkreuz as it is known is an award given out by the German government to honor individuals of solid character, those

who've made a substantial impact on German society or culture.

Schwartz insists that some mysterious, often veiled, but powerful energy would not let him die--and now, to reach the redemption and recognition of being honored by the German government is a story I'm quite sure would be rejected by Hollywood as far too implausible to be believed. The descendants of the people who once sought to exterminate him as part of the Nazi final solution have come full circle, not only validating his existence and worth as a human being, but honoring his struggle and cherishing his wisdom, realizing that in his experiences are vast treasures of knowledge that will prove crucial to the survival of humanity in a better, more just and humanistic world, one embracing tolerance and democracy--and even love.

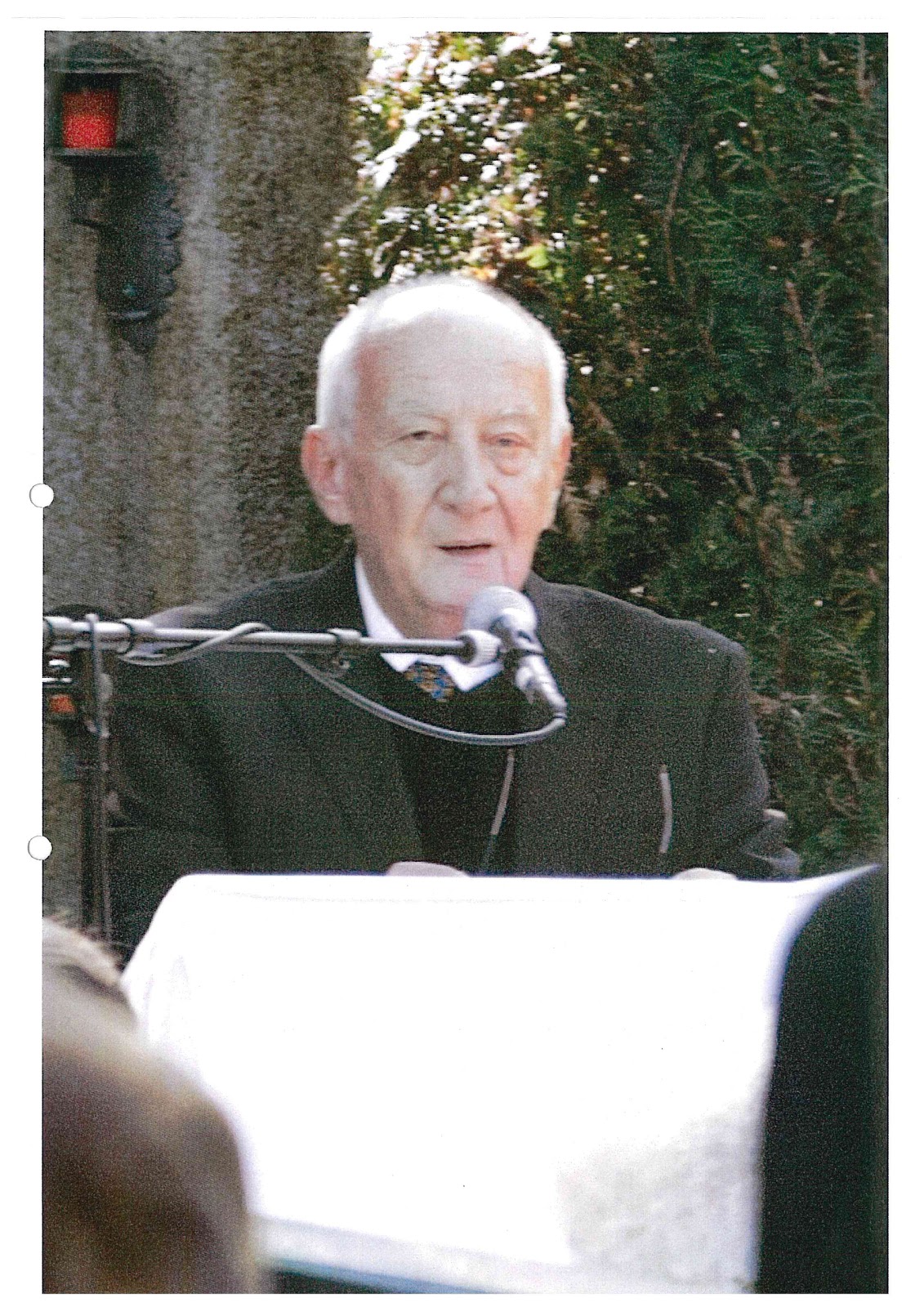

Despite being shot, slaved, tortured, and starved all before the age of fifteen, Leslie, well past eighty years of age now, is still active and still determined to tell his story, often jetting from one location to another as he is invited all over the world to speak at a plethora of events and memorials. Though it took more than sixty-five years for his voice to emerge, the work of being a witness, only begun in large part for Schwartz in 2010, has taken on great importance for him, "I realize I was not alone in thinking that I must live through this--the idea of becoming a witness is very prevalent among so many survivors."

Right from the earliest days after the war ended and for many decades afterwards, Schwartz was continually drawn back to Germany, back to the places where he had endured so much suffering, "I know it was really important for me to walk about Germany as a free man and mingle" but his connection to a new generation of Germans changed everything. He has made his notoriety in Germany by following the lead of his friend and fellow Muhldorf survivor Max Mannhiemer, who has spoken to tens of thousands of German students throughout the years. Schwartz has found healing and a sense of purpose in his relationship with Mannhiemer, an individual who had also been awarded many international honors such as the Knight of the French Legion, and especially from the students they meet. Schwartz believes he has a responsibility to educate them. He also believes the best prescription for healing is to help others.

A recent documentary by German filmmaker Beatrice Sonhuter debuted on Bavarian television in April 2012. The Muhldorf Train of Death features an in-depth look at the last days of the war and Schwartz' survival of the Poing massacre as researched by six German teenagers, guided by their history teacher, one of Schwartz' heroes, Henry Meyer of the Markt Schwaben school (located near Poing, where the massacre took place all those years ago). The students develop a relationship with Schwartz as they uncover details about the atrocity, searching records before the Americans arrived. Mayer is just one of the modern-day heroes for Schwartz as he has met many Germans who work tirelessly to restore the memory of the Jews murdered during the Holocaust and bring those issues to the forefront of German culture today, even as Jewish communities made of mostly Russian immigrants revive Jewish culture in Germany. In a moment's notice, Schwartz will speak of people like Dr. Stephen Wanner (mayor of Tutzing) and Albert Hingerl (mayor of Poing), along with Henry Mayer, as just a few individuals who've helped bring about this renaissance of healing.

Schwartz insists that some mysterious, often veiled, but powerful energy would not let him die--and now, to reach the redemption and recognition of being honored by the German government is a story I'm quite sure would be rejected by Hollywood as far too implausible to be believed. The descendants of the people who once sought to exterminate him as part of the Nazi final solution have come full circle, not only validating his existence and worth as a human being, but honoring his struggle and cherishing his wisdom, realizing that in his experiences are vast treasures of knowledge that will prove crucial to the survival of humanity in a better, more just and humanistic world, one embracing tolerance and democracy--and even love.

Despite being shot, slaved, tortured, and starved all before the age of fifteen, Leslie, well past eighty years of age now, is still active and still determined to tell his story, often jetting from one location to another as he is invited all over the world to speak at a plethora of events and memorials. Though it took more than sixty-five years for his voice to emerge, the work of being a witness, only begun in large part for Schwartz in 2010, has taken on great importance for him, "I realize I was not alone in thinking that I must live through this--the idea of becoming a witness is very prevalent among so many survivors."

Right from the earliest days after the war ended and for many decades afterwards, Schwartz was continually drawn back to Germany, back to the places where he had endured so much suffering, "I know it was really important for me to walk about Germany as a free man and mingle" but his connection to a new generation of Germans changed everything. He has made his notoriety in Germany by following the lead of his friend and fellow Muhldorf survivor Max Mannhiemer, who has spoken to tens of thousands of German students throughout the years. Schwartz has found healing and a sense of purpose in his relationship with Mannhiemer, an individual who had also been awarded many international honors such as the Knight of the French Legion, and especially from the students they meet. Schwartz believes he has a responsibility to educate them. He also believes the best prescription for healing is to help others.

A recent documentary by German filmmaker Beatrice Sonhuter debuted on Bavarian television in April 2012. The Muhldorf Train of Death features an in-depth look at the last days of the war and Schwartz' survival of the Poing massacre as researched by six German teenagers, guided by their history teacher, one of Schwartz' heroes, Henry Meyer of the Markt Schwaben school (located near Poing, where the massacre took place all those years ago). The students develop a relationship with Schwartz as they uncover details about the atrocity, searching records before the Americans arrived. Mayer is just one of the modern-day heroes for Schwartz as he has met many Germans who work tirelessly to restore the memory of the Jews murdered during the Holocaust and bring those issues to the forefront of German culture today, even as Jewish communities made of mostly Russian immigrants revive Jewish culture in Germany. In a moment's notice, Schwartz will speak of people like Dr. Stephen Wanner (mayor of Tutzing) and Albert Hingerl (mayor of Poing), along with Henry Mayer, as just a few individuals who've helped bring about this renaissance of healing.

|

| "This is where my healing started, by trusting and believing in the new generation of Germans." |

In the end Schwartz is a survivor who refuses to see anything about his life or experiences in negative terms, even the Germans who sought to murder his entire family were never thought of as inherently evil, perhaps only that the country had gone collectively insane. In fact, three German civilians made indelible impressions on him during the war, going out

of their way to offer him kindness and food in his most desperate

moments in the camps. A farmer woman named Agnes Riesch brought him bread while Schwartz was imprisoned in Dachau. The SS told her, "if you keep this up, we'll put you in here." She replied, "I'm old. I don't care." Barabra Huber offered him milk and the most delicious bread and butter he ever ate in her rural farmhouse near Poing, just before the Hitler Youth burst through her doors and Schwartz took off running, only to be gunned down in Huber's pasture and brought back to aforementioned Muhldorf death train. With all that happened and his sudden departure, he didn't learn Huber's name for more than sixty-five years, but she never left his memory for one day. These women acted as surrogate mothers to him, treating him with compassion and solictitude beyond anything imaginable given the times. A man named Martin Fuss also befriended Schwartz in Allach (near Dachau) offering him Liverwurst sandwiches and friendship while Schwartz worked at the railroad station. Fuss had a son about Schwartz' age, and he could not turn away when he saw Schwartz in his moment of need. Schwartz kept in touch with Fuss and Reisch for many years after the war, and now Schwartz spends almost every waking moment finding ways to give back to their descendants, the young people in Germany, as if to repay the kindness offered him by those Righteous Gentiles he encountered.

Schwartz desperately wants to make his life meaningful, to know with certainty he survived for a reason. To come to any other conclusion seems to do a great disservice to the memory of the millions and millions who perished at the hands of the Nazis, including his mother, sisters, and step-father. He believes in a very humble way that a divine force has always looked out for him, bringing people into his life at just the right moment, affecting subtle yet powerful changes and future outcomes and that his survival carries a responsibility to speak out--it always has--and Schwartz is among the child and teen survivors who are now facing the end of their lives with a great sense of purpose to do just that. He is here to teach us something, lessons apparently we still need to learn if current history is any indication. In short, this sense of "otherness" must be dealt with and debunked once and for all. Use all human experience. No voice is to be discarded. It takes focus and hard work to maintain humanistic and democratic values. Our collective grip on civility is tenuous even in the best of times.

The notion that everything happens for a reason and that even the most horrible experiences can be used to create something good requires a great deal of faith, but Schwartz' faith has been validated, albeit almost seventy years later, "It is a great feeling to receive this award. In my wildest dreams I never thought about such a thing. I realize that they appreciate what I am doing."

Schwartz desperately wants to make his life meaningful, to know with certainty he survived for a reason. To come to any other conclusion seems to do a great disservice to the memory of the millions and millions who perished at the hands of the Nazis, including his mother, sisters, and step-father. He believes in a very humble way that a divine force has always looked out for him, bringing people into his life at just the right moment, affecting subtle yet powerful changes and future outcomes and that his survival carries a responsibility to speak out--it always has--and Schwartz is among the child and teen survivors who are now facing the end of their lives with a great sense of purpose to do just that. He is here to teach us something, lessons apparently we still need to learn if current history is any indication. In short, this sense of "otherness" must be dealt with and debunked once and for all. Use all human experience. No voice is to be discarded. It takes focus and hard work to maintain humanistic and democratic values. Our collective grip on civility is tenuous even in the best of times.

The notion that everything happens for a reason and that even the most horrible experiences can be used to create something good requires a great deal of faith, but Schwartz' faith has been validated, albeit almost seventy years later, "It is a great feeling to receive this award. In my wildest dreams I never thought about such a thing. I realize that they appreciate what I am doing."

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are reviewed first before being posted. If you would rather contact me personally, please e-mail me at marcbonagura@gmail.com